The Unemployment Error

If you are like me, you keep close tabs on the employment market. For years the BLS unemployment data is something I have taken into intake meetings with my hiring managers. In fact, I’m on record as recently as November as saying this was a best practice.

When I saw March’s unemployment numbers, I was surprised like everyone else. But I assumed that the BLS would have a hard time keeping up with the unprecedented number of unemployed people to account for in such a short period. The unemployment numbers are not simple to get to in the best of times. When a crisis hits and the BLS is trying to measure an event that has no parallel in modern history, I was inclined to give a little leeway.

However, the 13.3% unemployment number recently reported seemed to me to be just wrong. How could there be such a disparity between unemployment claims reported by the states and the number presented by the BLS? The BLS doesn’t initially show you the number result, just the percentage.

When I dug into the data, I found that they based the 13.3 percent on a 21 million person unemployment count.

Now, for the record, that is bad enough, but it is a far cry from the 40 million reported unemployment claims. Now 19 million isn’t a rounding error.

So I endeavored to understand exactly why there was such a disconnect. Some of it came together quickly. Furloughed people, for example, collect unemployment. But it isn’t obvious to count them as unemployed. There is going to be some fraud in the system, but even with the best explanations, I couldn’t bridge the gap.

The story

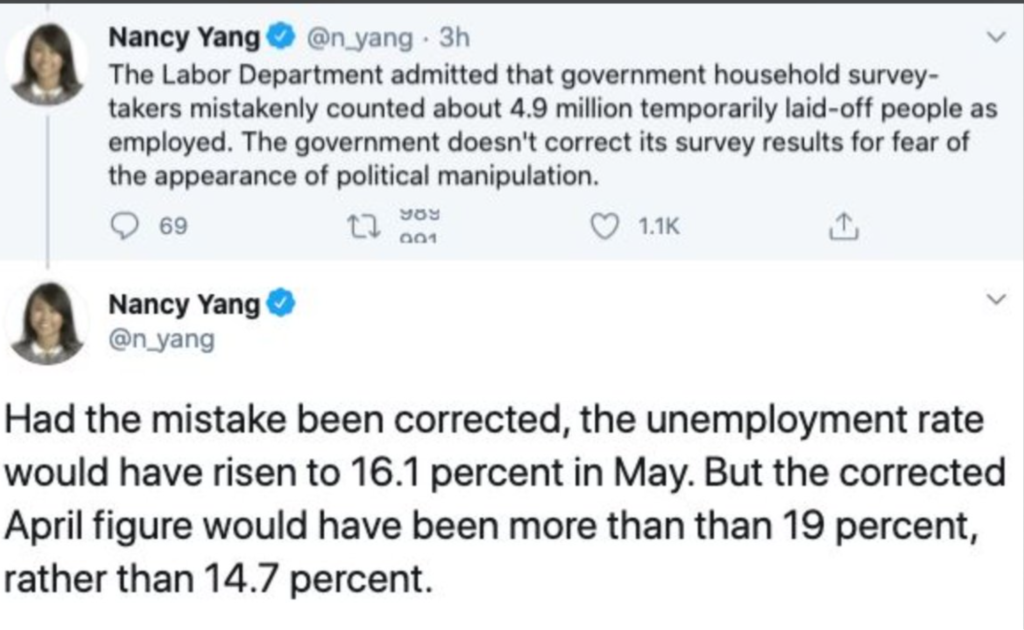

Then a story broke, and someone put this onto my timeline. It is a story by Nancy Yang, a reporter for MPR News.

Now, this is an entirely different story.

Temporarily laid-off is a very specific term for the BLS, but it normally does not have a lot of people in it. In this case, the error seems to be that they counted the people in this category as employed. That is a definition set by the BLS itself and reflects a decision made a long time ago as to what the definition was and how to count it in regards to overall unemployment.

No one expects the BLS to be perfect. Mistakes are made, and even big mistakes. This is a hard thing to do, and it is made more complex in the current condition. The BLS has a long history of self-identifying and self-correcting mistakes to their data. It is common practice to see preliminary numbers, final numbers, and then revised numbers from the BLS. The mistake, in and of itself, isn’t that shocking.

What is shocking is that they knew about it and didn’t correct the data. Their posted explanation that they didn’t update to not look political is actually an atypical response from them as noted by those of us who follow this data closely. In real terms, this is the single largest reporting error made by the BLS.

4.9 million counted as employed when they are unemployed is a massive error. It moves April’s unemployment number from 14.7% to 19.7%. Economists had been predicting 20%, and when the new numbers came out, it caused a credibility problem. That is quite a margin to be off by.

How will the BLS respond?

Now to be clear, no one expects the BLS to be perfect. We do expect them to be transparent. Burying a 4.9 million person mistake in the footnote while not updating the headline is misleading at the very best.

There is an obvious and instant political implication, but in reality, that is just the first challenge the BLS faces. Forbes interviewed me on this topic, and I’ll repeat what I said there.

“It’s going to be a problem of credibility now with the BLS,” said Mike Wolford, Director of Customer Success at Claro Workforce Analytics. “[BLS] looks incompetent or political. Twenty million people didn’t finish unemployment in the last 30 days. I would have thought lag time was an explanation because it’s a lot to count actually, but to find out they made a five-million-person error, knew about it, didn’t correct it for the sake of ‘data integrity’ when they literally update things all the time. That is suspicious and, at least, merits investigation,” Wolford added.

Needless to say, there are now going to be investigations, if not by Congress, certainly by investigative journalists. The problem now for the BLS is that there isn’t a good answer for them. No conclusion makes them look better or restores faith in their credibility.

You can bet that Wall Street will have its own analysts scrutinizing the data. They have taken the BLS on faith for years, and now it seems, that faith has been shaken. The implications are far-reaching. But, if the stock market loses faith in the BLS data about unemployment, then that will introduce a large unknown factor in the market.

One thing markets hate is uncertainty.

The ball is now in the hands of the BLS. How they respond to this “error” is going to establish or destroy their credibility longer term. For the near future, it means we are going to have to develop new methods and tactics for getting at this type of data. It is also a wake-up call to embrace an attitude developed by accountants during the Enron / Author Andersen scandals.

Trust, but verify.

Authors

Mike Wolford

As the Talent Intelligence Titan with over 15 years of progressive experience, I've dedicated my career to revolutionizing the talent acquisition landscape. My journey, marked by leadership roles at esteemed organizations like Claro Analytics and Twitter, has equipped me with a deep understanding of recruiting, sourcing, and analytics. I've seamlessly integrated advanced AI technologies into talent acquisition, positioning myself at the vanguard of recruitment innovation.

Recruit Smarter

Weekly news and industry insights delivered straight to your inbox.