Just in Time Hiring

Most organizations expect to turn the hiring process on and off like a light switch as needed. During times of growth, a company will open requisitions once the need becomes urgent, which is usually too late. As a response, additional recruiters are hired immediately either on a contract or as full-time employees.

No Knowledge of Corporate Culture

New recruiters with little company experience and virtually no knowledge of corporate culture are then expected to at once turn around and hire the next wave of talent in short order.

Even organizations enjoying solid partnerships with contingent staffing vendors expect quick ramp-up and turn-around time. It becomes practically impossible for vendors to take the time required to evaluate candidates to present the highest quality available honestly.

Hiring top talent is the single most critical aspect of attaining growth with staying power.

Maintaining Quality of Hire

Maintaining a high quality of hire, while building and retaining a reliable employment brand enables organizations to be able to respond sharply to fast-changing talent acquisition demands.

It’s simply not feasible to recruit “on-demand” like that. “Just in time” hiring is a company-wide strategy. One built around creating a scalable pipeline that allows the talent into recruitment processes to ebb and flow, suitably matching demand.

Behind this seemingly intricate dance, the most critical piece is the care and maintenance of a candidate network. So that sufficient contacts within the prospective talent pool are kept warm and can be reached at the right time.

To achieve the delicate balance between retaining the interest of prospective talent, yet not set unrealistically high expectations, organizations must begin by empowering recruitment to be connected to all levels of the company.

As long as the talent acquisition function maintains strategic relationships with company leadership, hiring managers, and the candidate network, hiring “just in time” is possible.

Appropriate Forecasting Increases Demand For Talent

With appropriate forecasting of increased demand for talent, a recruitment organization can quickly scale up. By engaging an already expectant pool of talent, instead of starting over from scratch each time needs change.

In this article, we will examine an infrastructure that fosters “just in time” project-based hiring. And evaluate a strategy for rapid ad hoc deployment of special hiring teams in such an environment.

The Talent Landscape

A solid strategy begins with a clearly defined plan. At the foundation of a plan is nonambiguous language, that one can easily communicate. There is a rampant misconception we must dispose of in the employment marketplace before conveying a “Just in Time” strategy. That is the damaging myth of the passive candidate.

There is no such thing as a passive candidate.

So-called passive talent is a fantasy used to conjure up a kind of prospective employee that has taken little or no initiative to find an opportunity.

In short, the term “passive” candidate is used to describe a potential employee that needs recruiting before they would consider a particular employment opportunity. If they are not in a position to consider the opportunity at all, then they simply are not a candidate. For that opportunity, or at that time.

Suspects, Prospects, Candidates, and Applicants

There are four distinct types of talent in the marketplace. Aside from their suitability for the new role, these four types are stages. Separated only by the amount of time or energy, they will invest in search of that new role.

These four types can occur in anyone at different times in their career. And individuals frequently shift from one type to another during the recruitment process.

Progressing from left to right on the diagram above, the amount of time and effort dramatically increases from one stage to the next.

A lead (suspect) would quickly turn away from an opportunity, especially in the case when presented with the amount of time they would need to invest in interviews and completion of paperwork before recruitment. A prospect, however, is willing to consider investing some time to participate in exploratory phone calls.

The candidate, investing much more time into the process, would be willing to attend interviews. But may balk and lose interest if confronted with all the required paperwork.

In comparison, a prospective employee entering the process directly into the applicant stage is frequently willing to jump through all the hoops. Complete lengthy forms online, even when they feel they have a slim chance of receiving a call back from a recruiter.

Potential employees may enter this process at any of the four points.

Or they may traverse through all four, but they must be treated differently at each stage.

The most “passive” of applicants could have begun as a suspect or lead where they did not initiate the process themselves. Instead, they received an initial cold call from a recruiter, for example. Upon recruitment, they became a prospect because they felt this was a compelling opportunity, and it was the right time to explore it.

If it isn’t the right fit or the right time, the lead would have never become a prospect. Instead, smart recruiters treat many of those contacts as resources. Keeping them in their network so they can produce referrals. Or be re-approached once their situation changes or the timing is right.

After some preliminary phone conversations either now or in the future. They may become a candidate, attend interviews, and potentially complete the necessary application process.

This is the most resource-intensive approach since the lead identified by an expert researcher referred or somehow obtained by a knowledgeable recruiter. Who followed up with several time-consuming attempts to contact. One of which leads to an initial recruitment conversation.

The future employee would have then received additional attention from the recruiter, to convert them from a prospect to a candidate. And of course, the candidate would also invest plenty of their own time in calls, interviews, and through the application process.

Alternatively, a prospective employee may apply directly without being approached initially by a recruiter. And proceed in the manner standard to that company.

A passive candidate is no more than an applicant.

Whether that is through an online process or via walk-in applications, they are taking the full initiative themselves. Thus they enter immediately into the Applicant stage. This is what would typically be called an “active” candidate.

A passive candidate, then, is really no more than an applicant approached directly and actively recruited for the right opportunity at the right time. An active candidate is simply one who eagerly applies for opportunities. Regardless if it is the right fit or at the right time.

Top talent may come from any part of this spectrum. Still, the largest population of untapped high-quality talent found where at least a moderate amount of effort required on the part of the recruiting organization.

There’s a middle area awash with ambiguity. Candidates take varying degrees of initiative depending on their perception of the opportunity or prospective employer. It is precisely because of that ambiguity that this middle area is where you find the largest return on investment of recruitment activities.

The Talent Pool

There is no linear relationship between the size of the talent pool and the amount of effort it takes to recruit talent. Therefore, an organization needs to define its talent landscape and identify the critical points where recruitment should focus.

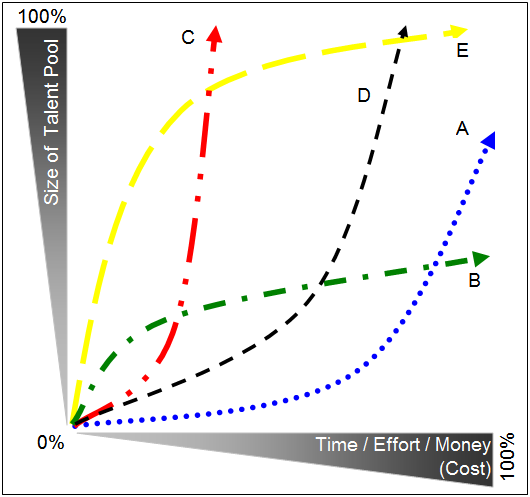

In the following diagram, imagine a straight line from the bottom left corner to the top right corner.

That line would represent the fictitious “perfect talent landscape.” The size of the talent pool available to an organization increases proportionately with the amount of time, effort, and money put into recruitment.

In actuality, a curve represents talent landscapes. Different segments of the working population would be represented by curves that demonstrate the reach of what portion of the talent pool with certain amounts of time, effort, or funds invested.

Such a curve, therefore, portrays the Return on Investment realized from varying degrees of recruitment activity.

Moving from left to right along the X-axis represents an increase in the amount of time, effort, or money required to recruit talent.

Diminishing Initiative

The increased cost is due to the diminishing amount of initiative prospective candidates will take when “shopping” for jobs. Thus making it so the organization intent on hiring that kind of talent will need to invest more in identifying, contacting, and recruiting.

The diminishing initiative, in turn, can be due to many environmental factors. Some of the strongest ones include the following:

- The difficulty of locating and contacting those types of candidates, particularly diversity candidates.

- Geographic or relocation issues.

- Competitors who recently increased demand for similar talent.

At the far right of the X-axis, candidates are almost entirely unwilling to participate in typical applicant activities like completing forms initially.

They are, for all intents and purposes, uninterested in exploring opportunities. These candidates are the most difficult, expensive, and time-consuming to engage. Yet frequently, they are of the highest quality.

The shape of the curve

The pool of available candidates grows vertically along the Y-axis, with the largest talent pool at the top. Some talent pools are much smaller than others. A fact viewable in the A and B example curves which terminate on the right-most end of the graph without ever reaching the top.

Varying segments of the working population will have different curves. Depending on experience level, education, location, and job function. Macroeconomic factors and demographics also play a significant role in changing the shape of these ROI curves.

As a result, some job functions will map differently at different times. One must take to re-evaluate the talent landscape and adjust strategies as appropriate regularly.

With that in mind, here are a few example curves and an explanation of what they represent.

– Curve A

This is a typical profile for recruiting highly specialized technical talent in industries like Information Technology, Software, Hardware, Biomedical, and Pharmaceutical.

This curve well represents professionals like engineers, researchers, and scientists. The size of the talent pool increases only after a significant investment. In these industries or job functions, it’s imperative to initiate communications with suspects. Expand the talent pool and recruit them into becoming prospects, candidates, and, eventually, applicants.

This is the costliest talent pool to expand. But one where the talent pool continues to increase quickly with added investment. As long as the potential talent pool continues to grow, it is worth investing additional resources and time.

This curve also shows a smaller maximum talent pool population than the others. Though not as small as that of Curve B.

– Curve B

This curve can represent many of the highly skilled professional fields like medicine and law. Additionally, it serves other job functions where career changes also happen less frequently as is the case with upper management and leadership positions.

In this example, an initial spike in the size of the talent pool occurs with little investment. Because when these types of candidates are looking, they know exactly where to go. However, following the curve, it quickly becomes apparent that significant increases in time and effort lead to small increases in the size of the talent pool.

This represents industries with a minimal talent pool where most candidates seldom take the initiative to seek out opportunities. That is unless a recruiter contacts them. Tapping into a larger talent pool becomes very costly in this curve.

The best return on investment for this example would be at about the point where the size of the talent pool no longer accelerates as quickly as it initially did.

– Curve C

This curve depicts many blue-collar talent landscapes. Like manufacturing, light industrial, construction, retail, transportation, food, and hospitality. And even some small business or office jobs.

A modest initial investment, like that of classified advertising, for example, dramatically increases the talent pool. A little more investment, like better advertising or a marketing and PR campaign, will quickly increase the talent pool available. So in this example, it’s appropriate to invest as much as the curve allows us to obtain the largest possible talent pool.

– Curve D

This curve exemplifies a different subset of the blue-collar professions, including more of the skilled or technical job functions like nurses, medical technicians, CAD operators, mechanics, etc.

These fields require a mid to high-level of investment. But the talent pool quickly broadens through referrals and word of mouth, especially once one establishes the reputations and relationships. The best return on investment here is right after the end of the curve as it moves up.

This is the point when word of mouth picks up momentum. And increases in the size of the talent pool are realized with fewer increases in time or effort invested.

– Curve E

One of the examples that this curve can represent is college recruiting. Regardless of the kind of degree, organizations hire large amounts of graduates and postgraduates right out of college. They find that with a small to moderate and fairly consistent investment, they can forge relationships with select educational institutions and recruit many top students from each graduating class. Small increases in time, effort, or funds invested will quickly broaden the talent pool.

However, recruiters must invest much more time, effort, and funds to get to the “cream of the crop” graduates from the top schools. Another example fitting this curve profile is when a large, highly branded “employer of choice” recruits mid-level professionals for their corporate headquarters.

Scaling Recruitment

Professionals in the city take note, and the word spreads fast when a city’s most reputable employer takes some initiative to recruit for job functions. Examples are in Corporate Finance, Accounting, Marketing, HR, PR, Legal, Sales, or any other Corporate HQ kind of role.

A small to moderate investment of time and effort opens the floodgates. People who usually don’t apply for jobs will apply directly and complete the application process.

Obtaining access to the largest talent pools can be prohibitively expensive, and it simply doesn’t scale. Organizations wishing to be able to scale recruitment up and down as needed based on “Just in Time” hiring requirements should not blindly drive to maximize their talent pool at any cost for every single role. You should not pipeline every role in an organization with this model.

Only pipeline multi-incumbent roles filled regularly. Recruitment efforts must focus on the most productive parts of these curves. Balance the cost and size of the talent pool.

Organizations that do this for their most critical roles will be successful in implementing “Just in Time” hiring.

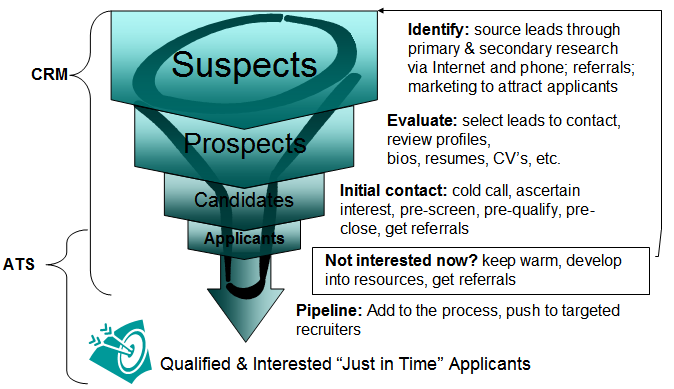

The Funnel

The funnel is one of the most commonly used metaphors to describe how organizations filter applicants. With a wide mouth at the top that allows volumes of people into the screening process, the idea is that the selection of candidates shrinks as they move down the funnel. The very best candidate falls out of the narrow end of the “candidate funnel” and becomes an employee.

While this is a useful metaphor when dealing with near-infinite amounts of applicants. It is absolutely useless for a “Just in Time” model where there is a limited talent pool.

There’s simply no way that you can fill the funnel from the top each time you open a new requisition.

Even if that were possible. After a few attempts, most of the available candidates would have been through the funnel once before. They will be unsympathetic to organizations that ask them to go through it time after time.

Just in Time Hiring

In “Just in Time” hiring, there is something similar to a funnel. The difference is that the “Just in Time” funnel operates more like a renewable hopper.

One where you bring people into the process or come in on their own at different stages of the recruitment life cycle.

The hopper represented above is a continuously full pipeline of candidates with suspects. As you identify new suspects, evaluate to see if they show potential.

If they do, you can initiate contact. And, if they show interest, feed that new candidate into the application process.

If they are not interested, then perhaps solicit additional suspects from that person. Or the suspect is simply put on hold, kept warm, and brought back in at a later time.

Store the suspect and prospect data separately from Applicant Tracking (ATS) data and treat them more like sales leads. They are not tied to a specific requisition until both the timing and the opportunity are a fit.

Once established, this pipeline begins to build upon itself. This makes maintenance more manageable and realizing economies of scale. At this point, scalability becomes most important.

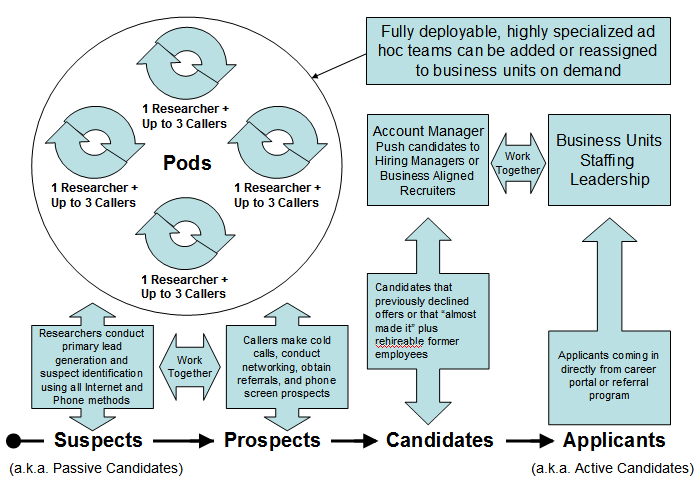

Scalability by Specialization

At the center of scalability lies specialization. Conduct suspect identification or lead generation by highly-specialized experienced recruiters who have become researchers. Their passion is for the hunt—the identification of primary and secondary information that leads to pockets of talent previously unidentified.

Researchers and Callers

Researchers’ single focus is to identify potential talent and obtain their contact details. Feed that information into a Contact Relationship Management (CRM) application and assign it to another highly specialized recruiter. A “cold caller” or “closer.”

These recruiters take the suspects or leads generated by researchers and evaluate them for specific roles. Then initiate contact with those who are a fit. Callers specialize in generating interest. Akin to salespeople, these recruiters are passionate about selling the opportunity to prospects and engaging their attention.

Callers may also work with other sources of prospects like employee referrals and special projects. When callers identify new prospects or suspects, they share further information with researchers. Who, in turn, could identify additional leads for the callers and find updated contact information.

Frequently, callers will obtain pieces of information or competitive intelligence while on the phone with prospects. That complements the work researchers are doing and enables them to penetrate deeper into untapped sources of talent.

Prospect into Lead Generation

If, during the phone conversation, there is no interest from either the prospect or the caller. Or the prospect is simply not a fit. Callers then attempt to make the prospect into a resource from which they can obtain additional leads.

They can also choose to make a note to revisit the prospect at a later day when situations have changed, and there may be a fit. If a candidate shows interest and willing to go through the interview process, present them to the hiring authority and the traditional evaluation process begins.

At this point, they are no longer an applicant. They are in the hands of either HR or the hiring authority.

Scale Up Recruitment Efforts

Because of this specialization, if hiring needs grow beyond the output capabilities of the researchers and callers, then bring in additional resources. Due to the sensitive nature of sourcing research and competitive analysis, the ideal situation is one where researchers are full-time employees, and the callers are either vendors or contracted labor.

This allows for the flexibility of being able to bring on board enough callers to scale up recruitment efforts. While the researchers simply increase their output. Since the pipeline, or the hopper, should be continuously filled, all the callers have to do is turn up the heat and revisit the contacts which have been kept warm. Along with working new leads, the researchers generate.

One researcher should be able to keep between one to three callers busy. In models where the amount of labor needed to identify talent is initially much higher. As would be the case with Curve B in the diagram previously discussed. The ratio could then be one researcher per caller.

Other Models

Other models, where obtaining a high volume of leads is a bit less labor-intensive, the ratio could scale up to as many as five callers per researcher.

Callers phone screen leads that go through the process from suspect to prospect. They are then sent to an “account manager” who presents them to the business units’ hiring managers or recruiters. Which, in turn, moves them into the hiring process, making them applicants. Thus completing the “Just in Time” recruiting process.

Some candidates may come back directly into the candidate stage because they are the “runner up” from a previous interview round. Or they received an offer in the past but declined it and are now willing to consider opportunities again.

Applicants may also get into the process by applying directly through the company’s standard procedure. But in this case, they would typically go straight to the business aligned recruiters or even to the hiring managers skirting the “suspect to prospect” dynamics of this model.

Below is a sample roadmap to guide in the construction of an ad-hoc, fully deployable, highly specialized just-in-time hiring team.

Authors

Shally Steckerl

One of the pioneers of the sourcing discipline, Shally is the Founder and former President of The Sourcing Institute, where he has helped numerous F500 and mid-market organizations train and develop their talent sourcing capabilities for nearly 20 years. When it comes to innovative approaches to candidate search, Shally literally wrote the book. He is the author of the industry-standard textbook “The Talent Sourcing and Recruitment Handbook” as well as “The Sourcing Method: Tactics to Find Unfindable Talent.”

Recruit Smarter

Weekly news and industry insights delivered straight to your inbox.